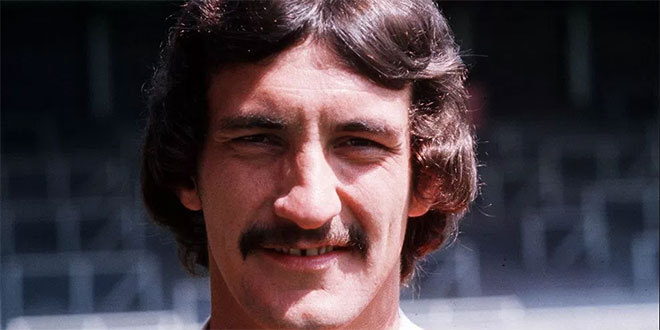

There is an evocative photograph of Terry McDermott which was caught on camera in the aftermath of the 1974 FA Cup final. In this photograph McDermott is stood on the Wembley turf, facing the royal box and wearing the red shirt of Liverpool; his arms are folded, his shoulders are low and his facial expression is set somewhere between thunder and desolation. Behind him the marching band are stood in formation, almost as if they belong to McDermott himself. Liverpool had just beaten Newcastle United in one of the most one-sided FA Cup finals of all time. The photograph was taken by the remarkably gifted Stephen Shakeshaft.

McDermott was in the Newcastle United line-up at the 1974 final. The Liverpool shirt he was wearing at around 5pm on 4 May had belonged to Phil Thompson for the duration of the game. On a day when Liverpool excelled and Newcastle United froze, McDermott was one of the few lights to shine in a black and white striped shirt. Six months later McDermott was the owner of his very own Liverpool shirt, when he became one of the first few signings made by Bob Paisley after he’d found himself unexpectedly in possession of the manager’s job at Anfield, in the wake of Bill Shankly’s shock resignation that July.

McDermott, like Thompson, the man he exchanged shirts with at the end of the FA Cup final, was born in Kirkby on the outskirts of Liverpool. Yet, whereas Thompson went on to work his way through the ranks at Anfield, McDermott slipped the net of both Liverpool and Everton, instead taking a more unorthodox route to the top of Merseyside, domestic and even European football. McDermott’s path to the Liverpool first team came via Bury and Tyneside.

After a difficult first two years at Liverpool, where both he and the club considered his future, McDermott was eventually involved in six league title-winning campaigns, won the European Cup three times to add to a UEFA Cup win, was twice a League Cup winner, while he also graced another FA Cup final. Other various trinkets were collected along the way: a European Super Cup and a cluster of Charity Shields. Twice the winner of the Goal of the Season award, he was the very first player to be named both the PFA and FWA Player of the Year in the same season and won 25 caps for England.

McDermott, to an extent, slips under the radar when it comes to discussions about the great Liverpool players of the 1970s and ’80s. Sharing a central midfield partnership with the gravitational figure of Greame Souness goes some distance to explain why that is the case, but McDermott’s other midfield colleagues for much of his time in the Liverpool first team were also ones that commanded attention and respect aplenty. The metronomic Ian Callaghan, the grace of Ray Kennedy and the power of Jimmy Case meant that McDermott slotted into what was quite possibly the greatest midfield unit the club ever fielded.

Unlike some of their rivals, McDermott’s Liverpool was all about the collective rather than small numbers of talismanic figures. While Arsenal could boast a Liam Brady, Tottenham Hotspur could rely upon a Glenn Hoddle and Manchester United could look to a Bryan Robson for inspiration, Liverpool spread the responsibility a little more evenly across the entire team. There were no pedestrians as such and the much vaunted ‘Liverpool Way’ almost bordered on a concept of football by communistic ideal, just as all the great club eras are. See the Total Football of Ajax, the modern-day Barcelona and the plethora of wonderful German periods of domination at both club and international levels for further examples.

McDermott essentially blended into a wonderfully talented community at Anfield. Behind him he had the excellent Ray Clemence, the dynamic effect of Emlyn Hughes, the effortless Alan Hansen, the commitment of Phil Thompson and the attacking intent of full-backs Phil Neal and Alan Kennedy. The latter of those full-backs had also been in the Newcastle side with McDermott for the 1974 FA Cup final against Liverpool. Then you have to consider what McDermott had in front of him in the final third of the pitch.

McDermott was blessed by the presence of Kevin Keegan and then Kenny Dalglish. He linked seamlessly with both, while the supporting cast included the likes of the powerful John Toshack, the vastly under-rated David Johnson, the speed and skill of Steve Heighway, the shock and awe that was David ‘Supersub’ Fairclough, and eventually a young striker by the name of Ian Rush, who would go on to score more goals for the club than any other player. Rather than stand out head and shoulders above his team mates, as he would have at any other club, McDermott’s talents were absorbed within an all-encompassing collective.

For this collective of players the honours rolled in like an avalanche, and McDermott was a crucial component. The peak of their powers was reached in 1978-79 and although the record books will tell you that Liverpool have had other more trophy laden seasons, that season offered a dominance and artistry in the league that was almost hypnotic. In early September a newly promoted and reinvigorated Tottenham Hotspur arrived at Anfield, not just with the blossoming Hoddle, but also with the recently signed Argentine World Cup winners Osvaldo Ardiles and Ricardo Villa.

Liverpool dismantled Tottenham in the glorious late summer sunshine, scoring seven times along the way. The seventh and final goal of the afternoon was scored by McDermott and it is widely considered to be the greatest Liverpool goal of all time. Defending a Tottenham corner in front of the Kop, McDermott was positioned on his own six yard line, the deepest outfield player in red.

Seventeen seconds later he is the foremost Liverpool player on the pitch, positioned on the Tottenham six yard line in front of the Anfield Road end to head home an inch perfect cross from Heighway. It was the climax to a move which involved just seven touches of the ball by six players once the Tottenham corner kick was taken. With such vision and precision the ball was moved from Thompson to Ray Kennedy then onwards through Dalglish, Johnson and Heighway before finding McDermott’s forehead, having sprinted the length of the pitch.

In a 42-game campaign Liverpool conceded just 16 goals, only four of those at Anfield, dropping just two points on home soil. They won 30 games. Had it been a title race contested in the three points for a win era, then Liverpool would have finished just two points short of the 100-point barrier. McDermott was at the very zenith of his career, yet it was arguably a four season zenith, where he scored over 60 goals between 1978 and 1982, also assisting in countless others for his team-mates.

McDermott was blessed with an array of skills. He was assured on the ball in a manner that suggested he had all the time in the world, but also hinted at just how fast the speed of thought process he was in possession of really was. He was a scorer of the most wonderfully majestic goals, all of which seemed to have a split second where McDermott almost looked like he had the advantage of pressing pause on his surroundings to assess his options, before pressing play again, flicking up a ball that rolls towards him and volleying home an arrowed shot from a few feet outside the angle of the 18-yard box into the top corner of the Tottenham goal at White Hart Lane. This was a goal that actually occurred in an FA Cup quarter-final in 1980. It was the only goal of the game and it won McDermott the second of his two Goal of the Season awards.

There was a litany of other McDermott goals that offered his unique artistry. Be it his drag back and cool chip against Everton in the 1977 FA Cup semi-final, or his running chip at Aberdeen in the European Cup in late 1980, or his surging and delayed run into the Borussia Mönchengladbach penalty area as he opened the scoring in Rome at the 1977 European Cup final. They only serve to scratch the surface of the talent McDermott possessed.

There is a myth surrounding the Liverpool midfield of McDermott, Souness, Kennedy and Case which suggests Souness and Case provided the bite and steel to McDermott and Kennedy’s artistry and vision. In reality all four players had both steel and skill in rich abundance. McDermott was no shrinking violet when it came to mixing it with opposing players and could more than hold his own in the heat of battle. He was at times at the very centre of such flare-ups.

The local lad was one the most balanced midfielders of his generation. As adept with his left foot as he was with his right, his sense of timing was immaculate and his vision to be able to play in his team mates extended to him being able to place a ball into parts of the pitch that they themselves may not have necessarily realised they were gravitating towards.

At international level McDermott travelled to both Euro 1980 in Italy and the 1982 World Cup in Spain. Playing an active role in Italy, he could only watch from the sidelines in Spain as Ron Greenwood instead opted for Robson and Hoddle for his central pairing, despite McDermott having played in most of the qualifiers that had got England to the finals. Competition for places was huge at the time and McDermott could easily have won double the number of caps had he played today.

Post 1982 World Cup and time at Anfield finally caught up with McDermott, just as it had with Kennedy and Case who had already moved on. Younger players were on the rise at Anfield with the likes of Sammy Lee, Ronnie Whelan and Craig Johnston picking off places in the Liverpool midfield. Before the year was out McDermott had departed the club, returning to a now Second Division Newcastle.

Back at St. James’ Park McDermott enjoyed being the pivot of the side that won promotion back to the top flight in 1984, teaming up again with Keegan and helping mentor the burgeoning talents of Peter Beardsley and Chris Waddle. Since their relegation in 1978 Newcastle had stagnated and the arrivals of McDermott and Keegan awoke the slumbering north-east giant. In January 1984 Newcastle travelled to Anfield to face Liverpool in the FA Cup; despite a 4-0 reversal it was a game that celebrated the emerging rebirth of the black and white stripes. Keegan retired after the promotion campaign, but McDermott would again play top-flight football for a short time.

Having eventually conceded his legs couldn’t carry him through top flight English football anymore, McDermott turned out for Cork City for a spell, before answering the call of his former Newcastle team-mate Tommy Cassidy, the man who’d partnered McDermott in the Newcastle midfield in the 1974 FA Cup final. Cassidy was in charge of APOEL in Cyprus and McDermott, along with former Tottenham striker Ian Moores, helped them to the Cypriot title and Super Cup success. McDermott’s career ended with yet more glory.

He later, and in some ways unexpectedly, went into coaching, drawn back to Newcastle when Keegan took the manager’s job in 1992. A temporary situation initially turned into a full-time return to the game, operating under a number of different managers at the Toon and later employed by Huddersfield Town, Birmingham City and Blackpool under Lee Clark. McDermott has gone full circle twice now and is back at Anfield on match days as part of the hospitality team.

Team is the predominant word that runs through Terry McDermott’s career. Individually exceptional, but always grafted to the template of a team set up. Within that concept he doesn’t always get the credit he truly deserves.

Steven Scragg

apoel.net Η συνήθεια που έγινε εξάρτηση

apoel.net Η συνήθεια που έγινε εξάρτηση